Ten remarkable new marine species from 2024

- The Mystery Mollusc, Bathydevius caudactylus

- The Divine Dragon Glistenworm, Chaetoderma shenloong

- The Mimic Worm, Cryptochaetosyllis imitatio

- The Freely Branched Pterobranch, Rhabdopleura emancipata

- John Hooper’s Carnivorous Sponge, Abyssocladia johnhooperi

- The Ranma Tanaid, Apseudes ranma

- Shimomura’s Bean-Shaped Isopod, Anthuroniscus shimomurai

- Scripps Cousins Wood-Dwelling Seastar, Caymanostella scrippscognaticausa

- The Paired-Lure Anglerfish, Gigantactis paresca

- The Chimera Mantis Shrimp, Incertasquilla chimera

Release date: March 19th 2025

Press release available at https://www.marinespecies.org/worms-top-ten/2024/press-release

High-resolution images of Top-Ten species available at https://marinespecies.org/photogallery.php?album=5636

The Mystery Mollusc

Bathydevius caudactylus Robison & Haddock 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1779673

A mighty mystery mollusc has finally been revealed. Captured by photographs but not conclusively studied until now Bathydevius caudactylus Robison and Haddock 2024 is a midwater gastropod whose identity and affinities had eluded definition for more than 20 years. Long seen on video and camera surveys in the midwater of the eastern Pacific Ocean and for years, simply referred to as the "mystery mollusc," Bathydevius caudactylus has a translucent white body topped with a large oral hood, an orangey red stomach and digestive gland, and a tail fringed with a dozen, finger-like projections that give the animal its specific epithet. The body of the mystery mollusc gives off blue bioluminescence.

Bruce Robison and Steven Haddock, scientists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), conducted the anatomical and genetic studies that finally solved the mystery, but their work has raised further intriguing questions. Bathydevius caudactylus is a nudibranch, an order of gastropods whose members are common in shallow water and in deep water benthic habitats but heretofore unknown in midwater ecosystems. Despite superficial similarities like a large oral hood, Bathydevius caudactylus is not closely related to the shallow-water hooded nudibranch Melibe, but instead represents an independent and early-diverging branch within nudibranchs. Other mysterious attributes for this mystery mollusc includes the absence of the rasping mouthplate (called a radula) and an extremely low rate of oxygen consumption, pointing to natural histories more like midwater floaters such as jellyfish and suggesting key, shared strategies for life in the deep open ocean. The mystery is not yet fully solved.

Original source

- Robison, B. H.; Haddock, S. H. (2024). Discovery and description of a remarkable bathypelagic nudibranch, Bathydevius caudactylus, gen. et. sp. nov. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 214: 104414: 1-8., available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2024.104414

- Steve Haddock (haddock@mbari.org) (co-author)

- Bruce Robison (robison@mbari.org) (co-author)

- https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&pic=184916&tid=1779673

- https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&pic=184921&tid=1779673

The Divine Dragon Glistenworm

Chaetoderma shenloong C. Chen, X. Liu, X. Gu, J.-W. Qiu & J. Sun, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1758091

At lengths exceeding 150 mm, Chaetoderma shenloong Chen, Liu, Gu, Qiu & Sun, 2024 is among the largest known members of the molluscan class Caudofoveatea. This is a group whose members are worm-like inhabitants of sediments that have tiny scales embedded in their skin rather than shells. The elusivity and elongate, scale-covered body of Chaetoderma shenloong recalls the mythical and mysterious Chinese dragon Shén Loong, known to many through its representation in the popular manga/anime series "Dragonball" and the source of the species' common name of "divine dragon glistenworm".

The team of describers, from the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Ocean University of China, and Hong Kong Baptist University, discovered Chaetoderma shenloong in sediments from a methane seep in the South China Sea; it is the first caudofoveate documented from chemosynthetic habitats. Although separated by more than 10,000 km and the landmass of Central America, Chaetoderma shenloong appears to be closely related to Chateoderma felderi, another giant caudofoveate described from the deep Gulf of Mexico. Earlier work on Chaetoderma shenloong, prior to its formal description, resulted in the first chromosome-level genome assembly for Caudofoveata (as Chaetoderma sp.).

Original source

- Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Gu, X.; Qiu, J.-W.; Sun, J. (2024). Integrative taxonomy of a new giant deep-sea caudofoveate from South China Sea cold seeps. Zoosystematics and Evolution. 100(3): 841-850., available online at https://doi.org/10.3897/zse.100.125409

The Mimic Worm

Cryptochaetosyllis imitatio Jimi, Britayev & Martin in Jimi et al., 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1762943

Imitation is often considered the sincerest form of flattery...or in the salty, aquatic realms, the best path to a free lunch. The newly described syllid worm Cryptochaetosyllis imitatio Jimi, Britayev and Martin 2024 lives on soft corals in the tropical reefs of the Indo-West Pacific Ocean. The body of these unusual worms is brightly colored, contains few segments, has small, simple chaetae and large, spindle-shaped dorsal cirri. Its closest known relatives have many more segments, shorter dorsal cirri and shorter, denser parapodia with large, jointed chaetae.

The highly modified appearance of Cryptochaetosyllis imitatio offers two intriguing possibilities. The color patterns and frond-like body appear to offer camouflage against the branching soft corals, suggesting crypsis as a means of avoiding detection by predators. However, the narrow body of this worm, its sparse but long projections along with the bright colors, strongly recall the morphology of nudibranch molluscs whose diet of cnidarian tissue and ability to sequester stinging capsules made by its prey offers a formidable defense against predation.

Although their modular bodies and ubiquity in marine and terrestrial environments would seem to make annelids good candidates for evolving mimicry, this is rare. Batesian mimicry, in which a harmless mimic evolves resemblance to an unpalatable or harmful model, is known from a few cases, and Müllerian mimicry, in which a mimic who is noxious or dangerous evolves resemblance to another, harmful model to amplify the advertisement of danger, is largely unknown in annelids. Examination of the dorsal cirri of C. imitatio, which closely resemble the cerata in which a sea slug sequesters the stinging capsules of its cnidarian prey, revealed that these contained no nematocysts. However, the authors could prepare only two specimens, and they are not ready to rule out Müllerian mimicry based upon this small sample. Jimi said, "If we could find more individuals, we could accurately determine whether this species is venomous. We will study the evolutionary process of C. imitatio to clarify which form (Batesian or Müllerian) was used to successfully acquire mimicry and why it mimics the venomous aeolid nudibranchs."

Although details of the interaction between the worms, their soft coral host, and nudibranchs remain to be determined, it seems likely that the unusual morphology of Cryptochaetosyllis imitatio helps them live in reef ecosystems packed with predators and competitors.

In the picture you see the new syllid worm species Cryptochaetosyllis imitatio on the left, compared to the nudibranch mollusc Coryphellina exoptata on the right.

Original Source

- Jimi, N.; Britayev, T. A.; Sako, M.; Woo, S. P.; Martin, D. (2024). A new genus and species of nudibranch-mimicking Syllidae (Annelida, Polychaeta). Scientific Reports. 14(1)17123: 1-11., available online at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-66465-4

The Freely Branched Pterobranch

Rhabdopleura emancipata Gordon, Quek & Huang, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1792710

Graptolite fossils are famously flat. The name given to this lineage is inspired by their defining signature - where fossils of the colonies leave scrawling markings on rock- and underscores that the biological interpretation of the fossils was long unclear.

The discovery of the connection between fossil graptolites and modern pterobranch hemichordates has helped to resolve some intriguing questions about this enigmatic group. Pterobranch hemichordates are colonial filter feeders, and, as their name suggests they are closely related to chordates, although the precise relationship between this lineage, echinoderms, and chordates remains somewhat unclear. Although graptolites were diverse and abundant enough to be useful as geologic index fossils, modern pterobranchs are not very species rich. The group was represented by eight extant forms prior to surveys in the deep water off New Zealand, which brought four new species to light.

Among the quartet of new species from New Zealand, Rhabdopleura emancipata Gordon, Quek & Huang, 2024 offers a morphology unknown among modern pterobranchs, with a colony composed of a three dimensional tangle of branches. All other modern pterobranchs have a colony that branches only along one surface. The growth form of Rhabdopleura emancipata offers important context for interpreting three-dimensional structure of the famously flat fossil graptolites.

Original Source

- Gordon, D. P.; Quek, Z. B. R.; Huang, D. (2024). Four new species and a ribosomal phylogeny of Rhabdopleura (Hemichordata: Graptolithina) from New Zealand, with a review and key to all described extant taxa. Zootaxa. 5424(3): 323-357., available online at https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5424.3.3

- Dennis P. Gordon (dennis.gordon@niwa.co.nz) (co-author)

- Huang Danwei (huangdanwei@nus.edu.sg) (co-author)

- https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&pic=184904&tid=1792710

- https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&pic=184903&tid=1792710

John Hooper’s Carnivorous Sponge

Abyssocladia johnhooperi Ekins & Wilson, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1773389

Although members of this group were described from the Challenger Expedition in the 19th Century, it wasn't until the 21st Century that the strange wonder of cladorhizid sponges was finally, fully appreciated. Unlike other poriferans, which feed on suspended particles or microorganisms, members of the family Cladorhizidae are carnivorous, actively catching and digesting prey using specialized spicules to hold prey until cells can swarm and digest the tissue. Harnessing improved camera systems and collections via remote or human-operated submersibles has enabled scientists to to learn more about the biology and related diversity of these fascinating cladorhizid sponges.

The voyage of the RV Falkor through the waters of Australia in 2020/2021 resulted in collections of many new species, including a black coral and sponge that were recognized as Top Ten marine species in 2022 and 2023. Now joining the ranks of Falkor-finds is Abyssocladia johnhooperi Ekins & Wilson, 2024, a carnivorous cladorhizid sponge. Like most members of Abyssocladia, Abyssocladia johnhooperi has a radiating, upswept umbrella-like crown atop a short stem. Genetic data from specimens collected by the RV Falkor, including Abyssocladia johnhooperi, shows that Australia harbors multiple lineages of deep sea carnivorous sponges and highlights the potential for biodiversity discovery, with multiple samples that were genotyped having no affiliation to any named species. Thus, the total diversity of Cladorhizidae remains dynamic, with new discoveries and new technologies likely to bring forth new species, and possibly new Top Ten winners, in coming years.

Original Source

- Ekins, M.; Wilson, N. G. (2024). New carnivorous sponges (Porifera: Cladorhizidae) from Western Australia, collected by a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV). Scientific Reports. 14(1): 22173., available online at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-72917-8

- Merrick Ekins (m.ekins@qm.qld.gov.au) (co-author)

- Nerida Wilson (Nerida.Wilson@csiro.au) (co-author)

The Ranma Tanaid

Apseudes ranma Matsushima & Kakui, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1762941

Sometimes scientific discovery can occur by chance - exemplified by Apseudes ranma, the Ranma tanaid. Tanaids are a group of crustaceans related to isopods and appear like an isopod stretched lengthwise. They belong to a larger group, Malacostraca, to which other crustaceans such as crabs, shrimp, lobsters, rolly-pollies, and krill belong.

This species was found in 2009 in the Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium where it had found its way into an aquarium tank. Since then, scientists have kept and bred these crustaceans for various studies. Through their research on this intrepid aquarium interloper, scientists discovered that it is not only hermaphroditic, which is unusual among crustaceans, but it is also the first species among the 67,000 species of malacostracans that is capable of self fertilization, making it able to reproduce without a mate.

In 2024, 15 years after its discovery in the Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium, detailed observations of the morphology confirmed that it is a new species. It was named Apseudes ranma, inspired by Ranma Saotome, a character in the Japanese manga Ranma ½. In the manga, Ranma can change sex back and forth from male to female when doused with boiling or cold water, which alludes to the hermaphroditic nature of this unusual Japanese crustacean.

Original Source

- Matsushima, Y.; Kakui, K. (2024). Apseudes ranma sp. nov. (Tanaidacea: Apseudidae) found in a public aquarium, with notes on phylogeny and a presumptive stridulatory organ. Bulletin of Marine Science. 100: 451–469; 25 July, 2024., available online at https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2024.0030

- Keiichi Kakui (keiichikakui@gmail.com) (co-author)

- Yoshinobu Matsushima (mattuu901@eis.hokudai.ac.jp) (co-author)

- Apseudes ranma sp. nov. (Tanaidacea: Apseudidae) found in a public aquarium, with notes on phylogeny and a presumptive stridulatory organ (Hokkaido University news)

- Official press release Hokkaido University

- New Species Of Crustacean Named After Rumiko Takahashi's Ranma (Anime News Network)

- Crustacean with Male and Female Parts Gets Named After Ranma (Otaku USA Magazine)

Shimomura’s Bean-Shaped Isopod

Anthuroniscus shimomurai Shiraki & Kakui, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1769070

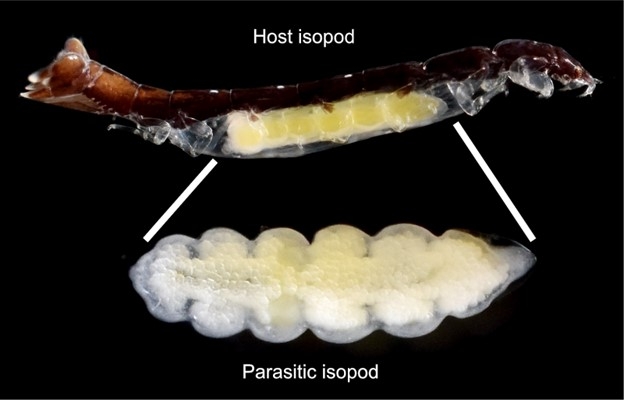

Isopods are a group of crustaceans that includes over 10,000 species, including the familiar terrestrial species known as roly polys, pillbugs, and woodlice. However, more than half of all isopod species live in the ocean, and some marine species have evolved parasitic lifestyles. Others have even taken their lifestyle to the extreme and no longer look like isopods or crustaceans at all.

The new species known as Shimomura’s bean-shaped isopod, or Anthuroniscus shimomurai, is one such example. It parasitizes the brood pouch of other isopods. The parasite has an elongated body, which is rare among parasitic isopods, and is probably an adaptation to the elongate body of its host. After locating a suitable host isopod, the parasite pushes out the host’s eggs and lives the rest of its life snug in the brood pouch of its host. This remarkable parasite was named after Dr. Michitaka Shimomura who has greatly contributed to the taxonomy of isopods in Japan.

Original Source

- Shiraki, S.; Kakui, K. (2024). Isopods on isopods: integrative taxonomy of Cabiropidae (Isopoda: Epicaridea: Cryptoniscoidea) parasitic on anthuroid isopods, with descriptions of a new genus and three new species from Japan. Invertebrate Systematics. 38(8): IS24013., available online at https://doi.org/10.1071/is24013

Scripps Cousins Wood-Dwelling Seastar

Caymanostella scrippscognaticausa Shen, Koch, Seid, Tilic & Rouse, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1778444

Much of the deep seafloor is like a desert, where food is scarce and life is scattered. However, when branches, logs, or even entire trees sink to the seafloor, they create underwater oases, hotspots for life, including for the newly described Scripps family wood-dwelling seastar, Caymanostella scrippscognaticausa—one of three new species in this genus described this year in the same paper.

Unlike the familiar starfish found in tide pools, these unusual sea stars have evolved some remarkable adaptations for life on sunken wood. Their bodies are flattened, their mouths are enlarged to maximize close contact with their woody home, and they have specialized spines that help them hold on. Despite their clear connection to wood falls, one big mystery remains—what do they eat?

Scientists are still unsure whether these sea stars feed directly on the wood itself or if they prey on other animals or microbes that colonize decaying wood. What is clear, however, is that they are part of a highly specialized community that is dependent on the breakdown of wood in the deep sea.

Caymanostella scrippscognaticausa is named in honor of the younger members of the Scripps family “Cousins for Causes” who generously supports ocean research. Discoveries like this highlight how much remains unknown about our oceans. With so much to be discovered, marine biologists around the globe are grateful to all those who support ocean science, including funding agencies, onors, journalists, and curious readers like you.

Original Source

- Shen, Z.; Koch, N. M.; Seid, C. A.; Tilic, E.; Rouse, G. W. (2024). Three New Species of Deep-Sea Wood-Associated Sea Stars (Asteroidea: Caymanostellidae) from the Eastern Pacific. Zootaxa. 5536(3): 351-388., available online at https://www.mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.5536.3.1

The Paired-Lure Anglerfish

Gigantactis paresca Rickle, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1796972

Around 1,000 meters below the ocean surface, lives a truly remarkable creature—the newly described deep-sea anglerfish, Gigantactis paresca. Collected during a 2021 research expedition led by oceanographers at the University of Hawai‘i, this strange fish was discovered in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, a vast region of the Pacific Ocean allocated for deep-sea mining.

What makes G. paresca particularly fascinating is its unusual lure morphology—unlike any other known anglerfish, it possesses not one but two bait-like structures. While many anglerfish are known for their long, bioluminescent lures used to attract prey, G. paresca has a second, non-glowing lure, an unprecedented trait that inspired its species name paresca, meaning “pair of bait.”

Adding to the intrigue, deep-sea ROV observations of closely related anglers suggest this species swims upside-down, using their elongated lure to scan the seafloor for prey. The jaw structure of G. paresca further supports this theory, as its large, backward-curving lower teeth would function effectively as an upper jaw when inverted. Though anglerfish like this typically live at great depths, recent ROV efforts have revealed more Gigantactinid sightings, providing hope we will soon discover a lot more about the biology of these unusual fish and other deep-sea life.

Original Source

- Rickle, S. Z. (2024). A New Species of the Anglerfish Genus Gigantactis (Lophiiformes: Ceratioidei) from the Clarion Clipperton Zone of the Eastern North Pacific Ocean, an Ecosystem Threatened by Deep-Sea Mining. Ichthyology & Herpetology. 112(2)., available online at https://doi.org/10.1643/i2023056

- Samantha Rickle (szrickle00@gmail.com) or (szrickle@hawaii.edu) (co-author)

The Chimera Mantis Shrimp

Incertasquilla chimera Ahyong, Nakajima & Naruse, 2024

https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1760042

The Chimera mantis shrimp, recently discovered off the coast of western Australia and Japan, is a member of one of the most fascinating groups of marine predators—mantis shrimp. Mantis shrimp boast some of the most complex eyes in the animal kingdom and wield one of the fastest strikes in nature—some species can punch with a force comparable to a .22 caliber bullet.

However, rather than delivering powerful punches, the Chimera mantis shrimp, Incertasquilla chimera, is of the spearing variety of mantis shrimp. Armed with large, spiny raptorial claws, it strikes with lightning speed to skewer unsuspecting prey.

Even among mantis shrimp, this new species is exceptional. It is so distinctive that scientists created a new genus for it, and it does not even clearly fit in any existing mantis shrimp family. In fact, its species name chimera comes from the fact that it exhibits different features found in several groups of mantis shrimp. This discovery broadens our understanding of mantis shrimp diversity and raises important new questions about the evolutionary history of some of the ocean’s most exciting predators.

Original Source

- Ahyong, S. T.; Nakajima, H.; Naruse, T. (2024). A new genus and species of mantis shrimp from Australia and Japan (Crustacea: Stomatopoda), with a revised diagnosis of Tetrasquillidae and a key to its genera. Journal of Crustacean Biology. 44: ruae038., available online at https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/ruae038

Acknowledgements

The WoRMS Top Ten Marine Species 2024 would not have been possible without the collaboration between the WoRMS Data Management Team (DMT), the WoRMS Top Ten Decision Committee, the WoRMS Steering Committee (SC) and voluntary contributions by many of the WoRMS editors.

WoRMS – as ABC WoRMS – is an endorsed action under the UN Ocean Decade.

WoRMS and Ocean Census have a partnership to enhance rapid discovery and identification of marine life.

WoRMS is listed as an affilitated project with Marine Life 2030, which is endorsed as an UN Ocean Decade Programme.

The Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ) is the permanent host institute of the WoRMS.